The Road Not Travelled:

By John Hearin |

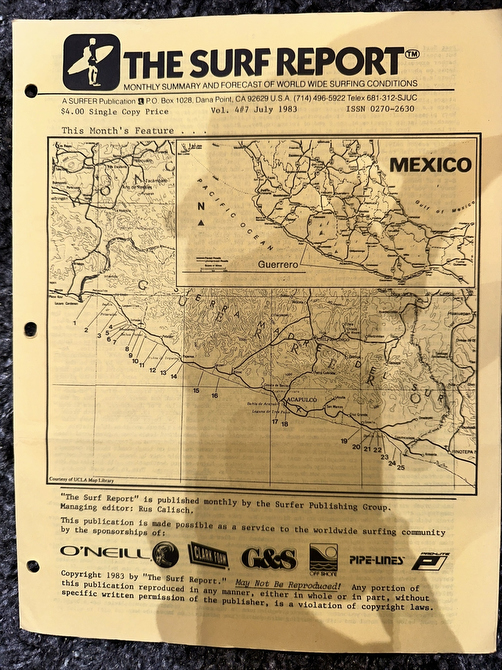

It was late afternoon in August of 1994, the peak of the rainy season in Costa Rica. As I stared out from the bank of another nameless river in the Nicoya Peninsula, rain drops began to ping off the roof of my truck. My destination, Playa San Lugar, was on the other side of that river. At least I hoped it was. In the days before cell phones with GPS and Google Maps, it was hard to know where exactly you were in Central America. I had been assured by two locals on horseback a few miles back that this was the right road. As described in my tattered copy of “The Surf Report”, Playa San Lugar was “… a long stretch of totally uncrowded beach breaks. Here you will definitely surf alone”. Those empty waves would be all mine in the morning, if I could make one more river crossing before dark. Off to the east I could see towering thunder clouds looming over the highlands. It was raining hard up there, and the river before me was no longer a sluggish creek like so many I had crossed earlier in the day. With rising trepidation, I threw my truck into low 4-wheel drive and plunged into the river. As an avid surfer from Cocoa Beach, Florida I had dreamed of making this trip for years. Inspired by stories in surf magazines and movies, I yearned to make my own “Surf Safari”. By 1993, I was 33 years old and had been working as an aerospace engineer on the NASA Space Shuttle launch team for eight years. The 1990’s were a bull market on Wall Street and when I gazed at my 401K statement, I could not believe that I had amassed, what seemed to me at the time, the staggering sum of $60,000. So, with blatant disregard for my financial future and against the advice of virtually everyone I knew, I quit my job, sold or gave away everything that was not related to camping or surfing, cashed in my 401k retirement plan, and set out for Mexico and Central America in my 1985 Toyota SR5 4x4 pickup truck. My truck had an aluminum topper over its 6-foot bed with a ladder rack mounted on top for my quiver of surfboards. This truck would be my home for the next 12 months. For guidance I relied on a 3-ring binder full of issues of “The Surf Report” for each surfable coastline between Florida and Panama. For those readers who have never experienced life without the Internet, “The Surf Report” used to be published by Surfer Magazine. Each issue was printed on yellow paper that looked like something they would give you in grade school. They included crude maps, sketchy directions, and loose descriptions of the more worthy surf breaks in a region or country. To augment those reports, I had a collection of Rand McNally Road Maps whose accuracy diminished rapidly south of San Diego. Accompanying me on the first leg of my journey was my rugby teammate Peter, who hailed from the western suburbs of Sydney, Australia. Peter had been living in Cocoa Beach for the past year, working construction and playing rugby with the Space Coast Rugby Football Club. I must credit Peter for introducing me to the notion of a walkabout. Turned out that quitting everything and travelling the world for a few years was a common activity for Aussies and Kiwis in their 20’s. This notion astounded most Americans who struggled to use their meager one or two weeks of vacation each year. Oddly enough Peter was not a surfer, but when I told him about my plans, he insisted on tagging along. After travelling west across the USA, the real adventure began in the deserts of Baja California. We hit most of the surf breaks listed in “The Surf Report” and eventually made our way to Cabo San Lucas. Peter had an Aussie accent so thick that most Americans thought his name was Pita, like the bread. Back in Florida, I had often found myself serving as an Aussie to English interpreter to the more provincial residents of Cocoa Beach who were unaccustomed to such Australian slang as “tukka” (food), “cruk” (sick), and “fair dinkum” (Google it). After a night of reveling at Cabo Wabo, the infamous night club owned by Sammy Hagar, Peter failed to return to our campsite. I figured either he had scored or was incarcerated. I found Peter at the Cabo jail, hung-over but otherwise fine. It turned out that he had tried to ask the local authorities for directions to a late-night taco stand but his version of English was so foreign to their ears that they rousted him for drunk and disorderly. We paid the fine and were on our way. Peter and I parted ways in La Paz, where I boarded the car ferry for mainland Mexico, and he continued his walkabout north into Canada.

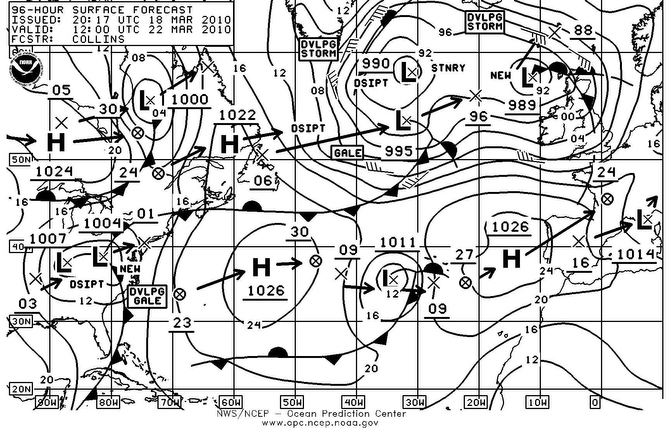

I surfed Sunzal in El Salvador by myself for several days before I got bored and went down to La Libertad. At Punta Roca I met a couple of Aussies, Chewy from Maroubra and Michael from Lorne. We surfed Punta Roca for several weeks and between us and three Israeli surfers, we were usually the only people in the water for dawn patrol. Surf Camps really didn’t exist at most of these places back then. At Popoyo in Nicaragua, Aussie Michael and I camped in an abandoned house right on the beach and we surfed the reef break by ourselves. I would end up staying with Peter, Chewy and Michael once I reached Australia, but that is a story for another time. Surf Fax By the time I reached Costa Rica, I had been on the road for eight months and considered myself a seasoned surf explorer. I was the only surfer at Witches Rock for several days until two carloads of gringos arrived in rented Suzuki Samurais brandishing a weather fax and promising swell. Before the advent of Surfline, surfers used to subscribe to weather faxes. The faxes showed the storms out in the oceans and turned many surfers into amateur meteorologists. I had been skunked so many times by weather faxes that I refused to believe in any swell that I could not see with my own eyes. Naturally the swell never materialized, and I proceeded to Tamarindo. After the empty waves of Nicaragua, the breaks around Tamarindo were a shock. Even 30 years ago, the rampant development of Costa Rica’s coastline was in full swing at this now popular tourist destination. On two occasions, I ran into surfers that I knew from back home. So, after a few weeks of sharing waves with half the state of Florida, I resolved that my next stop would be the vacant waves of Playa San Lugar, roughly 100 miles south on the Nicoya Peninsula. I left early, not realizing that nearly the entire route would be rutted dirt roads bisected with river crossings without any bridges. At the first river I encountered, I got out of my truck and waded to the middle of the river. It was only knee deep and barely flowing. I did the same at the next river. By midday I was plowing through rivers unheeded, like Marlin Perkins on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. Driving was slow and navigation was tricky. The road maps I had brought with me were useless once I ventured off the main roads. Back then travelers were forced to navigate the old-fashioned way, by asking for directions. Asking for directions in Central America invariably resulted in a local pointing in the general direction and telling you to go “directo”, or straight in English. Of course, before you had gone more than a few miles there would be a fork in the road, leaving you to wonder which “directo” he had meant. By late afternoon I found myself at one of those forks when two men on horseback rode up and assured me that the right fork was indeed the road to Play San Lugar. As soon as I entered the river, I could feel my Toyota begin to lose traction and start to drift downstream. My truck was now amphibious and the tires, poor excuses for paddles. I steered her upstream, luckily found a few shallow spots where I was able to get traction and tacked across the torrent. With dumb luck and a few hasty exhortations to all the known gods, I made it across to the far bank. Once safely out of the river, the “road” to Playa San Lugar devolved into a narrow path, and then a mud bog. There was no way I was going to cross that river again, I had no choice but to press on. Within minutes I was stuck up to my axles in mud. Before leaving on my Surf Safari, several knowledgeable off-roaders had advised me to get a winch for my truck. Electric winches were quite expensive, at least by my standards, so I had settled on a hand operated version, thinking I would probably never need it. That was a big mistake. That winch was useless and after struggling for the better part of an hour, I was still stuck. The two men on horseback I had encountered earlier came riding up. They were quite amused by my plight but offered to help. Eschewing the winch, they tied ropes around my bumper and tied the other ends around the horns of their saddles. With me gunning my engine for all it was worth and the two horsemen spurring on their horses, my truck eased its way out of the morass and onto dryer ground. The two men had a brief conversation, one wished me well and rode off. The other, whom I will refer to as El Caballero, explained to me that I should follow him closely and that he would lead me out of this mess. At least I think that’s what he said since my grasp of Spanish was only suited to ordering food and asking directions to “el bano”. The rain was now a torrential thunderstorm. I could barely see through the windshield as I power slid all over the trail, hard on the heels of El Caballero who was illuminated by bolts of lightning. Richard Petty would have been proud of the way I drove that Toyota right up until the point when I zigged when El Caballero had zagged, and a wave of water poured over the hood and instantly the truck stalled. I had driven straight into an unseen ditch full of water and the truck was stuck and would not start. El Caballero glared at me in disgust and said something that I imagined could be loosely translated as “what in hell did you do that for”? His countenance quickly softened, and he suggested that I spend the night back at his ranch. Mind you, my truck and its contents constituted all my worldly possessions and as much sense as his offer made, I simply could not leave my truck. I told him as much in my broken Spanish. El Caballero shrugged, shook his head, and rode off into the night. As I sat in the truck, the enormity of my situation began to sink in. My truck may never start again. No towing service was coming to get me. I might have to abandon the truck and walk out to civilization carrying whatever I could. Was this the end of my Surf Safari? As I pondered my fate in a vision of despair, I realized that water was flowing into the cab of my truck through the bottom of the doors. I could stay in that truck and spend a long night submerged up to my waist or I could get out and do something. I grabbed my backpack, sleeping bag, passport, what little cash I had, and waded out of the ditch. I started walking west and immediately came upon the beach. I had nearly made it! I could not have stalled out more than 100 yards short of the beach. I had made it to Playa San Lugar, but now what? The beach was empty except for one tiny light off in the distance. As I trudged up the beach it became apparent that the light was emanating from a fisherman’s shack. Without options, I walked up to the shack and knocked on the door. An old man answered the door. When I say old, he had the look of all the other fishermen I had seen in Central America. A lifetime at sea had leathered his skin, he could have been anywhere between 50 and 90 years old. I will call him “El Viejo”. El Viejo spoke no English, so I explained my predicament to him as best as I could and asked if I could spend the night in his house. Now put yourself in his shoes. You are alone in a secluded shack on an empty beach far from any town. Its dark and its stormy. A total stranger shows up at your door, wet, filthy, and babbling incoherently some wild story about a truck. Would you let him in? To his credit, El Viejo didn’t hesitate. He motioned me in and pointed to a spot on the floor where I could sleep for the night. Exhausted, I collapsed on the floor and went straight to sleep. Of course, nobody in rural Costa Rica lived by themselves. I was awoken shortly thereafter by the sound of his son, daughter in-law, and three grandchildren arriving from God knows where. I was way too depressed and weary to explain myself again, so I pretended to be asleep as the entire family gazed at this strange gringo who had materialized out of the gloom and was now sleeping on their floor. Morning broke clear and sunny, and after the obligatory introductions to my hosts, I wandered back to my truck to take stock of the situation. The water had receded somewhat, but the truck was still sitting in a deep ditch with water up to the wheel wells. It was going to be difficult if not impossible to work on her in that situation. As if on cue, another man rode up on horseback. El Caballero must have gone back to the ranch and told everyone about the crazy surfer who had drove his truck into a ditch. The horseman’s name was Jose, and he was the foreman at the ranch. Jose spoke some English and told me that he would return with his bulls to pull me out of the ditch. True to his word, Jose returned a few hours later with two oxen in a wooden yoke, just like in the westerns on TV. Jose and his oxen quickly towed my Toyota out of the ditch and up to the fisherman’s shack. I was so grateful for the help that I gave Jose all my cash, which was roughly $20 USD worth of Colones. Jose and his oxen rode off down the beach. I never saw them again. By this time, it was midday and El Viejo’s son Pedro offered me what help he could as I tried to resurrect my truck. As I had feared, the cylinders were full of water and the engine would not turn over. I had had the presence of mind to bring along a decent set of tools. I removed the spark plugs and when I turned the ignition, a gusher of water flew out of the cylinder heads. I squirted WD-40 into each cylinder, reinstalled the spark plugs, and cranked her up but she would not start. I repeated this process over and over. Each iteration she crept slightly closer to starting but after about the tenth try, my battery was dead. No further attempts at starting were possible. At this point Pedro told me about a white lady who lived a few miles down the beach. She owned a car, maybe she could help me? I set off down the beach with a glimmer of hope that this woman could be my salvation.

After walking and jogging a few miles down the beach I encountered the mouth of the river I

had forded the day before. It was high tide and the river was flowing steadily into the sea. At

first wading and then swimming, I managed to get across that river mouth and continue on

my quest. Another mile or so down the beach, I came to a house that was more modern

than El Viejo’s shack. I approached, calling out to anyone inside. The owner, a middle-aged

woman named Angela, greeted me at the porch with a surprised look on her face. She did

not get many uninvited guests to her beach house on Playa San Lugar. I spent a few

minutes explaining how I had arrived at her doorstep. She shook her head, laughed, and

told me that “nobody drives down that road”! It turns out that the left fork, where I had

initially met El Caballero, also led to Playa San Lugar. The left road was longer but in much

better shape than the mud bog I had traversed. She did have a truck, but she would have to

wait until low tide the next morning to make the trip to El Viejo’s shack. At low tide the river

mouth would be shallow enough that a 4-wheel drive vehicle could make it across, as long

as it was not raining up in the highlands. Thanking Angela, I retraced my path back to El Angela and her teenage son arrived the next day as promised. With jumper cables connected to my lifeless Toyota, I went through several more iterations of the spark plug and WD-40 routine until the engine sputtered to life. Steam poured out of my truck’s tailpipe like the whistle of an old train. I kept gunning the engine until I was convinced that she would idle long enough for me to collect my tools and bid goodbye to El Viejo and his family. The tide waits for no man, and we had to get down the beach while the river mouth was still passable. I had given Jose the rancher all my cash, so the best I could do was give my hosts all the food I had stored in my truck. I hugged each family member, knowing I would never see them again, then followed Angela down the beach, staying close in case my truck stalled again. We made it back to Angela’s beach house without further drama. She treated me to a delicious home cooked meal and a warm dry bed for the night. I finally surfed Playa San Lugar with her son the next morning. I honestly don’t remember what the surf was like. I left later that day for Boca Barranca, happy to be “back on safari to stay”. I learned two valuable lessons from my adventure in the Nicoya Peninsula. First, that the generosity of the Costa Rican people and the expatriates who have joined them, is boundless. Like a saltier version of Blanche DuBois, I had relied on the kindness of strangers to save me from a disaster of my own making. And second, never ask driving directions from a man on horseback.

|